Stories

Ci-dessous, vous pouvez accéder à nos histoires. Cliquez sur l'élément de l'histoire pour l'ouvrir en pleine vue. Raconter des histoires est un élément fondamental de l’être humain.

Archaos printed their own money, unfortunately no bars would accept it.

Archaos printed their own money, unfortunately no bars would accept it.

Archaos were often approached by various agencies who wanted to use the tent and performers as back drops for music videos and advertising campaigns. One such was a shoot for Haynes in Edinburgh 1990

Archaos were often approached by various agencies who wanted to use the tent and performers as back drops for music videos and advertising campaigns. One such was a shoot for Haynes in Edinburgh 1990

The first uber client Borkowski PR ever had was Archaos, the punk circus which scandalized the UK between 1988 and 1991 with dangerous chainsaw-juggling, a raunchy Gallic attitude and explosive, two-fingers-in-the-face-of Health & Safety performances. The UK circus scene was shaken to its very core and would never be the same again. And I’m proud to have been the impropergandist that crafted their media profile.

The groundbreaking campaign for Archaos was the foundation for the Borkowski ethos. One of the immutable things about the company is our attachment to a good yarn, a great tale, a strange story,...

The first uber client Borkowski PR ever had was Archaos, the punk circus which scandalized the UK between 1988 and 1991 with dangerous chainsaw-juggling, a raunchy Gallic attitude and explosive, two-fingers-in-the-face-of Health & Safety performances. The UK circus scene was shaken to its very core and would never be the same again. And I’m proud to have been the impropergandist that crafted their media profile.

The groundbreaking campaign for Archaos was the foundation for the Borkowski ethos. One of the immutable things about the company is our attachment to a good yarn, a great tale, a strange story, a bit of salacious gossip, a secret confidence, an odd anecdote or an outlandish rumour. We work with the stuff of conversation – the sort that fuels all social interactions. Barnum knew it, and he knew how to get conversations going to his commercial advantage.

We started out as theatre publicists who sought to follow in Barnum’s footsteps: getting bums on seats by getting people talking about stuff we got in the press. There wasn’t any money to mount costly media occasions or events, so we used guile and whatever creative means we could think of. We were relentless and ruthless in our pursuit of column inches. We ducked and weaved, thought fast and improvised.

We used stunts, hype, scams, and bizarre photo opportunities on the streets and we researched, promoted and invented every possible story angle in the search for ones that would secure coverage in every possible kind of media outlet. We didn’t restrict ourselves to targeting the obvious publications and programmes. We saw our job as spreading the word, wherever and whenever we could. We didn’t doubt that PR was a serious business but, at the same time, it had to be serious fun if it was to work.

The stunts were gripping, and they were absolutely expressive of the celebratory, life-affirming, invigorating and exciting spirit of the shows. People heard about what was happening on the streets, because we made sure – through gossip, whispered hints, press releases, questions in the house and whatever else it might take – that the media were on hand to witness it all. What was witnessed was published (how could they resist?) and anyone who had the slightest admiration for the edgy and the anarchic wanted to see these freaks in the flesh, and so they rolled up and Archaos played to packed houses wherever the production went.

BY ROBERTA MOCK

It was the summer of 1989 and my heart began beating double-time from the moment Archaos entered their tent on Edinburgh’s Leith Links. The maniacally grinning clown positioned two feet from my head started smashing a flaming baton against a metal tent support.

To my left, sparks were flying from a similar confrontation between a pole and a chainsaw. In the centre ring, the standard circus fire-breather jostled for attention with a whooshing blowtorch. A car exploded. At the climax of the show, a clarinettist descended head-first from the canvas heavens with one foot...

BY ROBERTA MOCK

It was the summer of 1989 and my heart began beating double-time from the moment Archaos entered their tent on Edinburgh’s Leith Links. The maniacally grinning clown positioned two feet from my head started smashing a flaming baton against a metal tent support.

To my left, sparks were flying from a similar confrontation between a pole and a chainsaw. In the centre ring, the standard circus fire-breather jostled for attention with a whooshing blowtorch. A car exploded. At the climax of the show, a clarinettist descended head-first from the canvas heavens with one foot in a noose.

I have always been wary of fire, heights and loud noises. I decided to remain in the audience of The Last Show on Earth, despite a suspicion that its title might be all too apt, because of a perhaps naïve faith in the safety of theatres, even temporary canvas theatres. And because the danger turned me on.

Archaos was the French circus that juggled chainsaws and generated acres of newsprint through a publicity machine that spewed out sensational stories of risk, madness and debauchery.

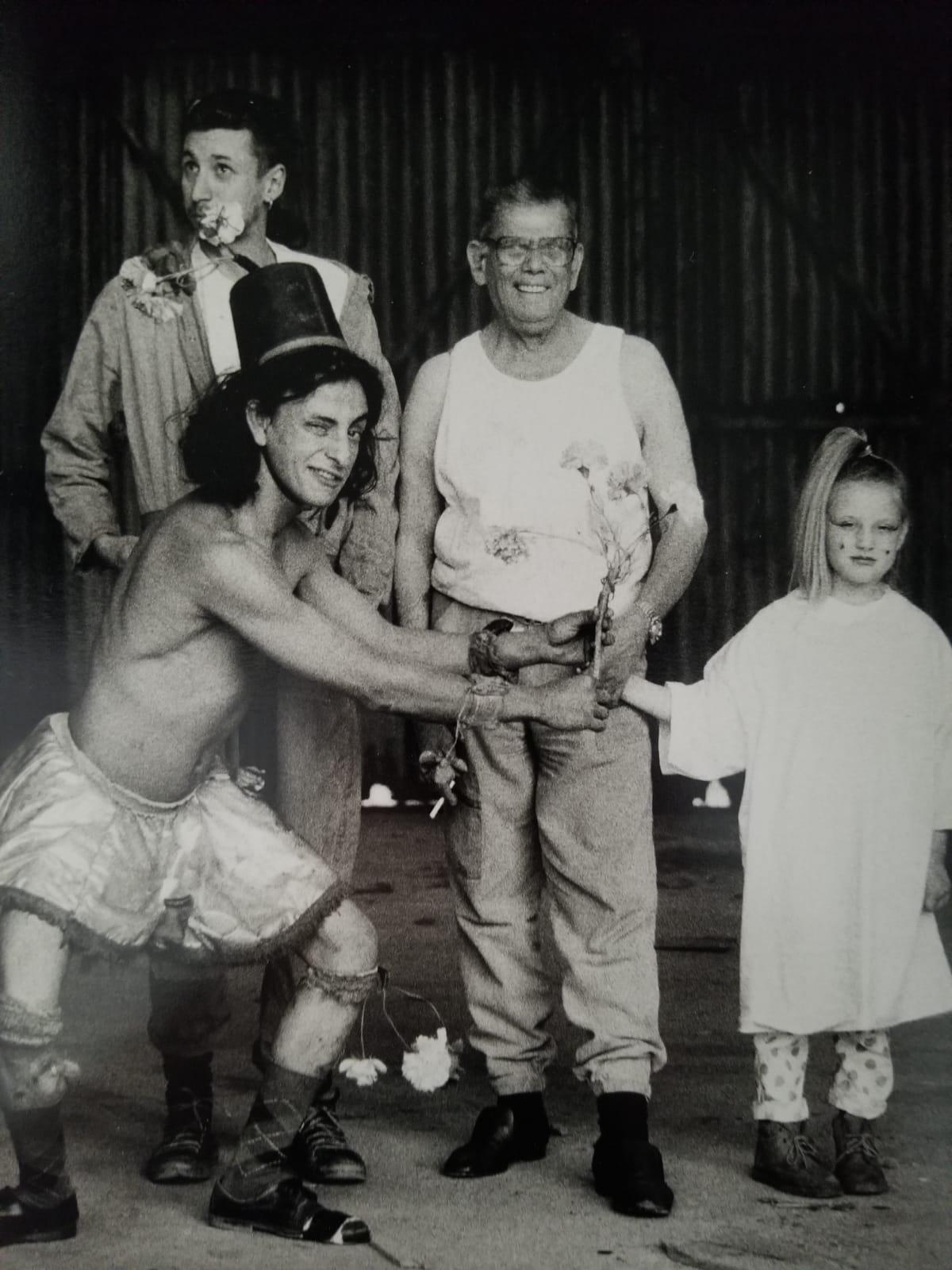

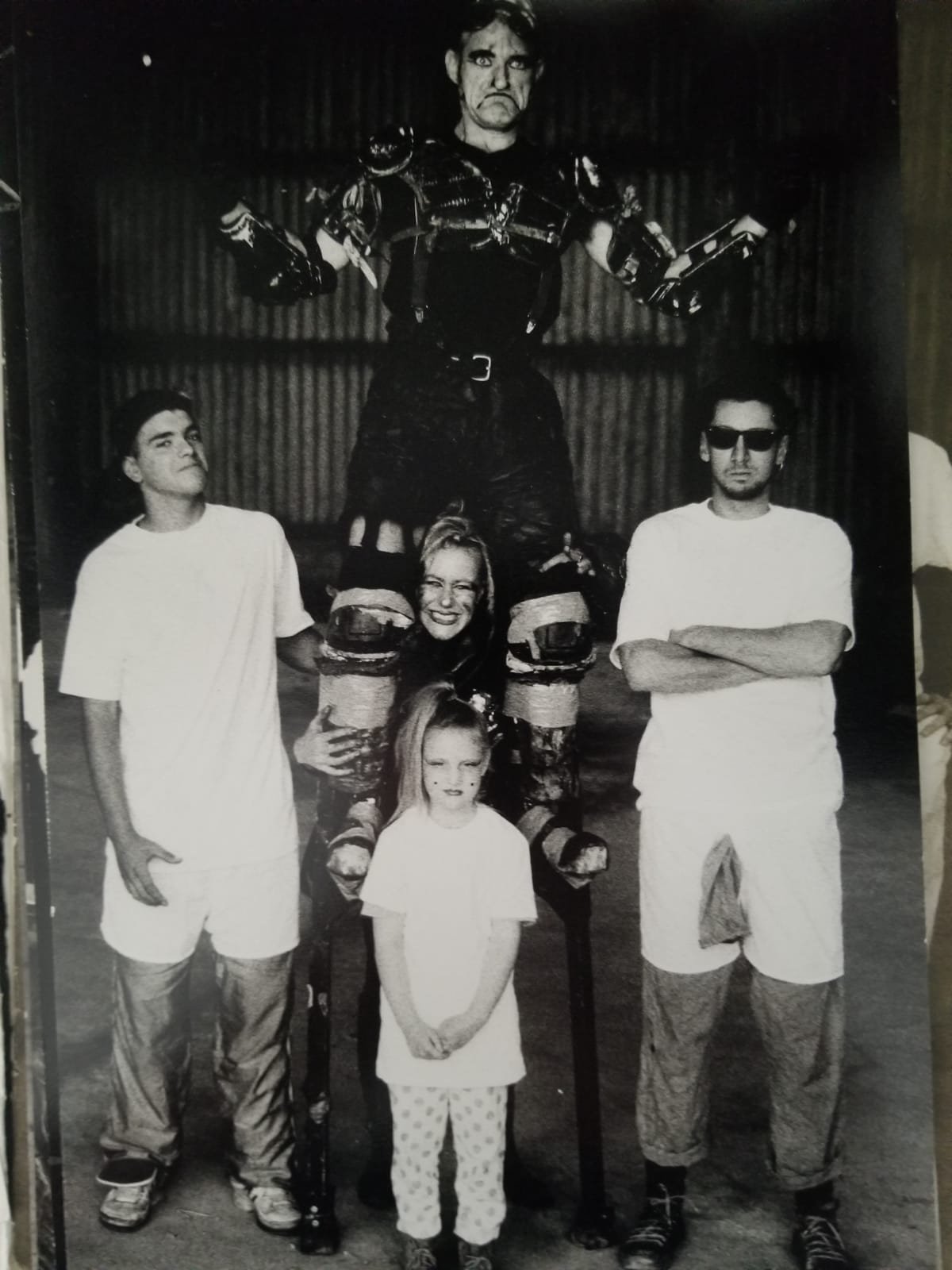

At the heart of this mythologization were the company’s corrugated-iron and leather clad Metal Clowns who decapitated one another, ignited firecrackers between their legs and engaged in despicable staged acts, like attacking a blind trapeze artist.

However, Archaos was always careful to balance infernal vision with the materialisation of uplift and transcendence: Jean-Paul Lefevre’s balletic trick cycling, the high wire mastery of Didier Pasquette, or Raquel and Ana de Andrade’s delicate pole-balancing, high above the audience and swathed in white cotton.

And Archaos also offered sex: raunchy, funny, hot, ridiculous. With his raccoon-like kholled eyes, wearing a leather vest and g-string, Pascalito Vionet employed a full-sized crane as a flying trapeze, before choosing a member of the audience, pulling her back by the hair and kissing her passionately until she gasped for breath.

Archaos’s dynamic stage world was complex and contradictory, embracing both ugly carnal violence and moments of intensely erotic beauty.

And so, as the barely clothed acrobats Gelbrich Bierma and Peter Van Valeknhoef wrapped around one another and lyrically mingled bodies in Bouinax (1990), a group of clown roadies masturbated under dirty raincoats. Jean-Claude Grenier, a dwarf with paraplegia, whizzed past the couple in his electric wheelchair, placing an apple in Valeknhoef’s mouth which Bierma shared upside-down.

For Adam and Eve, the snake’s gift of an apple meant a fall from grace and, like the snake, a person born with physical disabilities was once considered to be a portent of doom. Grenier, however, was a symbol of liberation who released the couple from the hell-on-earth inhabited by the debased and debasing clowns.

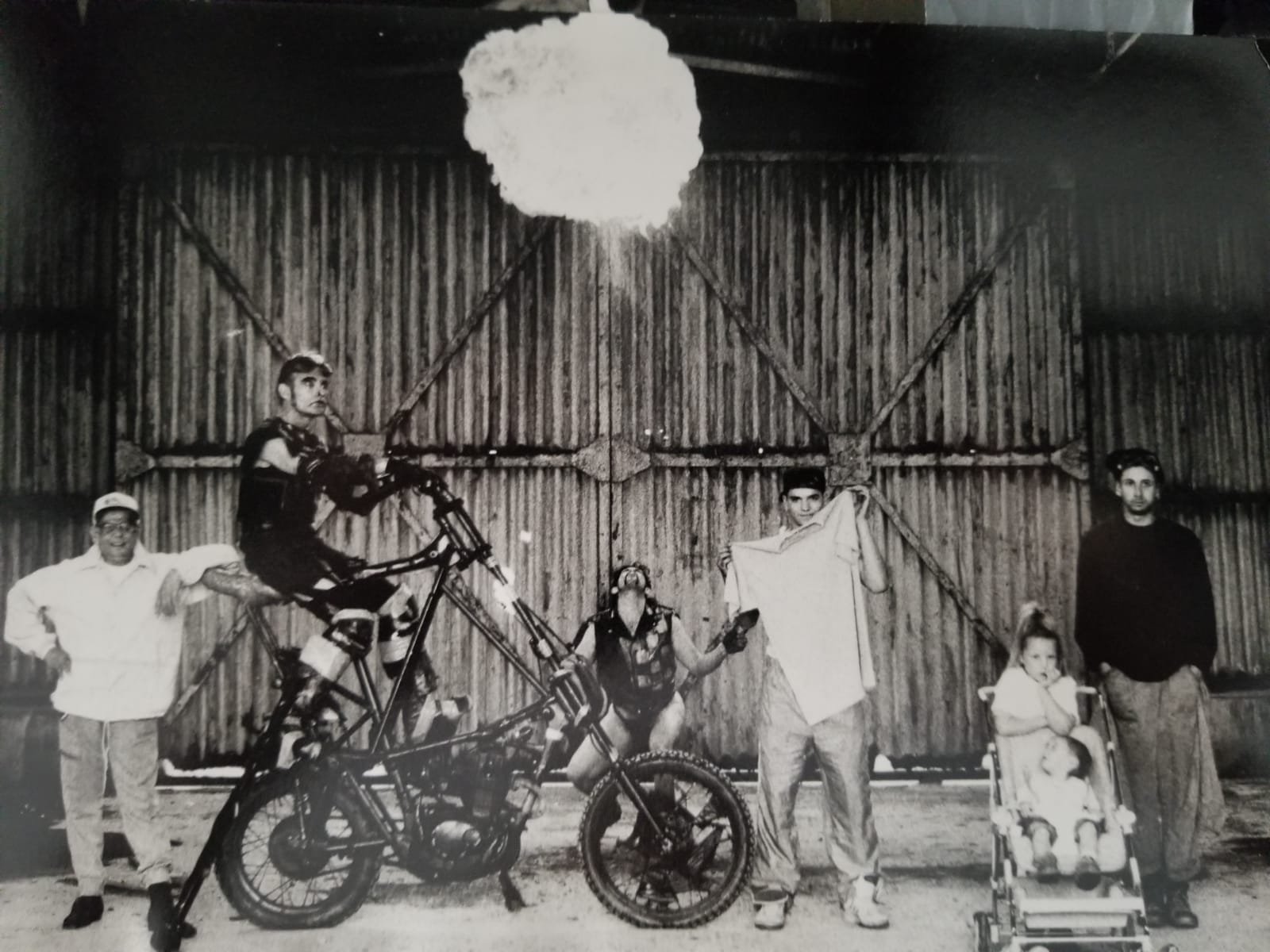

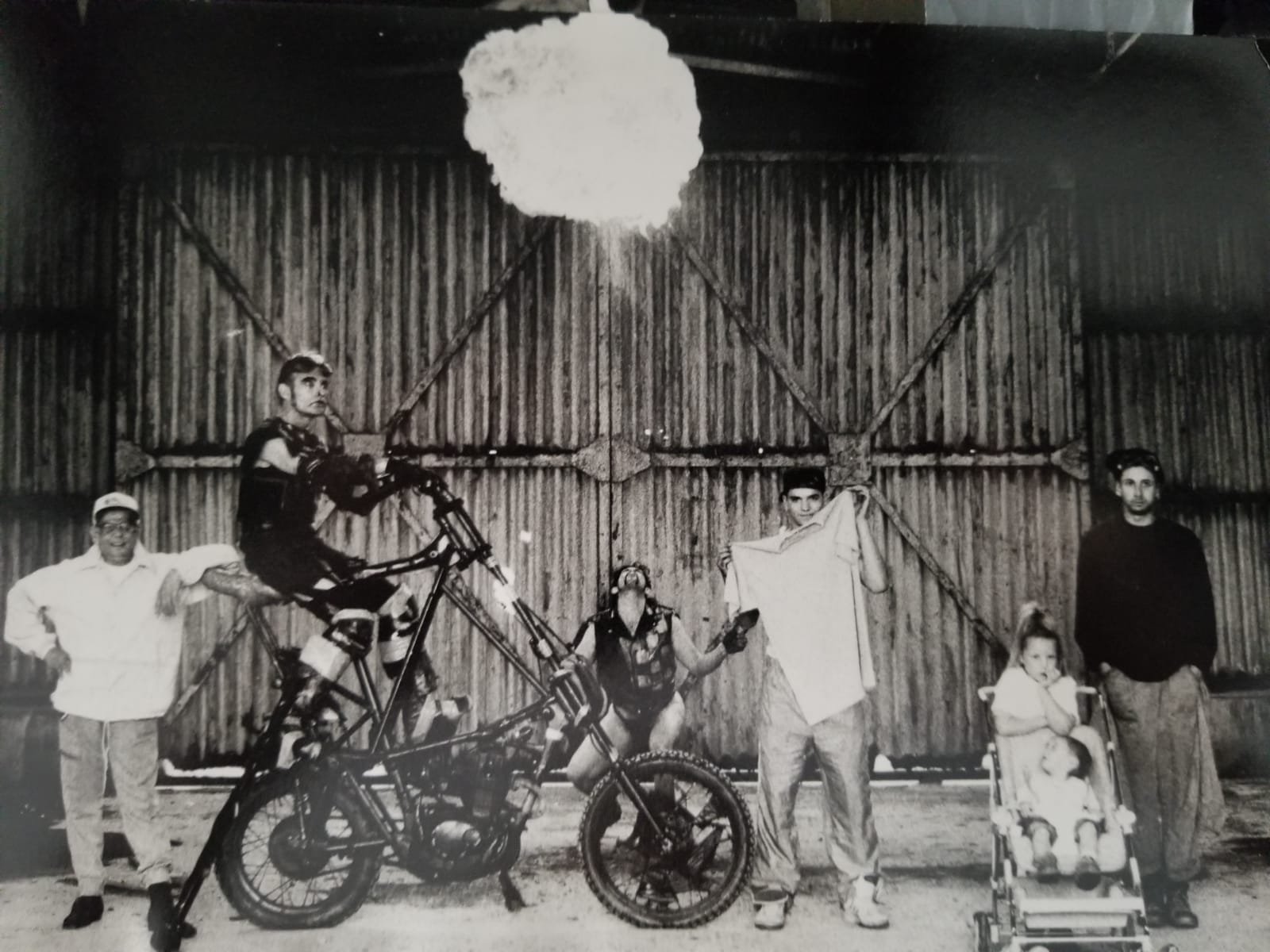

It was the horse that provided the impetus for modern circus in the 1770s, when Philip Astley, an equestrian who joined the English army as a rough rider, fashioned popular entertainment out of the legacy of war. Archaos accepted this inheritance; however, as purveyors of “new” animal-free circus (at least after their productions stopped featuring pigs, dogs and hypnotized chicken in 1988), the horse was swapped for its modern equivalent: the motorcycle.

It is no coincidence that Archaos’s 1991 show BX-91 was subtitled “Beau Comme la Guerre”. Their postcolonial “beautiful war” to a large extent remained Astley’s war of equestrian skill, now on two wheels. Archaos’s trick-rider, Stephane Depont, was clean, fresh-faced, and significantly wore sharply-designed grey leather; he controlled his machine gracefully and serenely, goading the engine and not the audience.

The Metal Clowns, on the other hand, were Hell’s Angels stripped of both motorcycles and expertise. With scrap iron strapped to their backs in lieu of “colours”, and unable to upstage the car through speed, they were reduced to destroying this bourgeois symbol through frustrated rage and senseless violence.

Beside the disciplined elegance of Depont’s motorcycle stunts, the clowns were manic and feeble, creating havoc because they had no real power. They were equally deflated by the present of Archaos’s gentle fools, such as Nordine Beckri who, wearing a tutu and plaster foot on his head, attempted to build a Greek temple around them.

When Archaos disbanded in 1992, my initial reaction was not that I would never be able to watch one of their shows again, but that one of my options had been swept from under me. My disappointment stemmed from the idea, deep down, that one day I would run away and join the circus.

Even given my phobias, this was not entirely implausible; Archaos often held open auditions when they rolled into a new town and they made it clear that they were receptive to like-minded individuals. Their press releases cited the case of the journalist who was sent to write about the company and ended up donning a jock-strap, jumping over fast-moving motorbikes and through flaming hoops under the stage name, “Dogman”.

Especially in their earlier shows, Archaos gave space to the dedicatedly mundane: a man who could squash a potato in his fist, or a person who could jump in and out of cardboard boxes elegantly, or just convincingly crack a whip and squeal.

It took many bodies to create a total attack on the senses and, for Archaos, sensory assault was not a vehicle for a message, but the message itself. Many critics seemed to both get and miss the point at the same time:

It is not theatre, but a spectacle of contradictions .… It seems to include everything yet comes to nothing. (The Scotsman, 1989)

The Archaos onslaught stuns by being so totally pointless yet totally absorbing. (The Scotsman, 1991)

The affect produced by Archaos was a disorienting combination of sensory bombardment and the annihilation of distance between audience and performance.

We deliciously tolerated having mackerel heads spat at us by a bleach-blond girl in flippers, or getting splashed when the rotund, hairy Archaos chef, Jean-Pierre Venet disrobed and showered in close proximity.

We accepted the strait-jacketed fugitive pursued through the bleachers by a chainsaw-wielding lover before being hauled into a wire cage. We allowed a young woman in a leopard-skin leotard to be plucked from our midst and decapitated, her twitching head pressed to a skinhead’s groin.

When one contemporary critic asserted that “Order, in fact, comes out of Archaos,” he was referring to the fact that the circus’s anarchic apparent recklessness belied the professional discipline which such a performance requires.

Archaos’s charismatic founder and father figure, Pierrot Bidon, passed away in 2010 and many of its performers died tragically young. I often find myself thinking about how our world still needs Archaos: a company that was simultaneously dirty, bonkers, inspired, brave, difficult, ambitious, spectacular, wild, loving and angry.

About the author:

Roberta Mock is Professor of Performance Studies and Director of the Graduate School at Plymouth University. Her essay, “When the Future Was Now: Archaos within a Theatre Tradition,” first published in 1994, was recently included in The Routledge Circus Studies Reader, edited by Peta Tait and Katie Lavers (Routledge, 2016)

Est ce que vous connaissez l'histoire du clown qui n'a plus de nez ? Non, et bien je vais vous la raconter. Lorsque j'ai senti le coup sur mon menton, je savais que c'était fini. Un coup de tronçonneuse, on a pas idée avant d'en avoir pris un de l'effet que ça peut faire, surtout quand on le prend dans la gueule. La gueule, c'est par définition l'endroit de son propre corps qu'on voit le moins. On pourrait penser que ça coupe, mais ça ne fait pas du tout le même effet qu'un rasoir ou qu'un couteau, la chair...

Est ce que vous connaissez l'histoire du clown qui n'a plus de nez ? Non, et bien je vais vous la raconter. Lorsque j'ai senti le coup sur mon menton, je savais que c'était fini. Un coup de tronçonneuse, on a pas idée avant d'en avoir pris un de l'effet que ça peut faire, surtout quand on le prend dans la gueule. La gueule, c'est par définition l'endroit de son propre corps qu'on voit le moins. On pourrait penser que ça coupe, mais ça ne fait pas du tout le même effet qu'un rasoir ou qu'un couteau, la chair n'est pas tranchée nettement, ce n'est pas aigu comme sensation, ça ne larde pas. Un coup de tronçonneuse, ça frappe, ça déchire, ça mord, ça griffe. C'est un peu comme un coup de batte de base-ball sur laquelle il y aurait des dents de crocodile. Il faut dire que se faire couper une cigarette au bec avec une tronçonneuse pour faire un ultime pied de nez au cirque traditionnel, ça comporte tout de même quelques risques et une part de folie, cette folie punk que nous avions à l'époque, la folie de ce spectacle, une traduction délirante de la folie du monde et de la folie du public. Malgré la brièveté de ce moment, la quantité de pensées qui m'ont traversées l'esprit est incalculable. Le silence qui nous entourait avait quelque chose d’irréel. Nous étions planté là, au milieu de la piste, entouré au bas mot de 2000 personnes et c'est pourtant un des plus grand moment d'intimité de toute ma vie. Un de ces moments ou on sait que nos vies et que le cour de l'histoire vient de basculer. Le souvenir du regard de Jason, les bras ballants, la tronçonneuse encore fumante à la main, ce regard, ce regard que je n'oublierais jamais... Quand j'y repense aujourd'hui, quelques vingt cinq ans après, il semble me dire tout à fait autre chose que ce que j'y ai vu sur le moment. Aujourd'hui j'ai l'impression qu'il me disait : « Va, je te libère, je te sauve la vie, part pendant qu'il en est encore temps, ça va mal finir et tu le sais, alors va, va »... Alors que sur le moment, son regard exprimait toute la détresse de quelqu'un qui vient malencontreusement de blesser son ami. Un regard d'une tristesse infini, un regard qui voudrait dire tellement, mais qui, au vu des circonstances, ne pouvait rien dire. D'ailleurs, la seule chose qu'il m'ait dit après m'avoir embrassé c'est : « Je crois que tu devrais sortir »... Et je suis sorti, ma dernière sortie, la plus belle, la plus théâtrale, la plus longue, la plus silencieuse, une sortie pour moi tout seul, dans un silence pesant, hors du temps, hors de moi, hors de tout. Je sentais la lumière et la chaleur des poursuites qui me suivaient, je sentais sur ma nuque le souffle coupé et les regards de toute la troupe et je marchais vers la sortie, vers l’extérieur, dans un calme irréel qui allait se terminer au moment précis ou j'allais franchir la porte. Tant que j'étais dedans, c'était calme, presque sans bruit et pour une fois la fureur se trouvait à l’extérieur, mais il fallait que je sorte, je n'avais d'autre choix que d'affronter ce « dehors » tout en sachant qu'une fois le seuil franchi, je ne pourrais plus jamais retourner à l’intérieur et ce fut le cas. J'aurais voulu faire pause, retourner en arrière, rester là, encore, encore un peu, mais le cour de ma vie m'attendait. A l'instant même ou j'ai pousser la toile de la porte, le spectacle à redémarré, je me suis mis à pisser le sang et les quelques personnes qui étaient dehors me sont tombées dessus. C'était super agressif comme sensation, je sais que c'était pas le but, mais des gens qui te sautent dessus pour te rassurer en te disant que c'est rien et que ça va aller, c'est tout sauf rassurant. J'ai envoyer chier tout le monde copieusement, je voulais juste un rétroviseur, me voir dans un miroir, voir l'ampleur des dégâts et personne ne voulait me laisser voir mon propre visage. J'ai saisi un mouchoir que quelqu'un me tendait, j'ai compressé mon menton, je suis rentré dans une voiture et je me suis regardé. Une belle cicatrice au menton, pas nette, un peu en dentelle, en escalier, à l'image de l'histoire quoi et deux minuscules griffures sur le nez, minuscules et énormes en même temps, comme une menace invisible, une tronçonneuse de Damoclès, une épée mécanique grondante suspendue au fil de mes décisions. J'ai refusé d'aller tout de suite à l’hôpital, j'ai attendu que Jason, Boris et les autres clowns de tôles sortent, je voulais voir Jason avant de partir, je savais dans quel état il devait être, en miette, avec cette culpabilité terrible, terrassante, je voulais le serrer dans mes bras, lui dire regarde, c'est rien, quelques points de sutures tout au plus, t'inquiète pas. Il était comme fou, il ne voulait pas continuer, il ne voulait pas re-rentrer, il répétait en boucle : je viens de mettre un coup de tronçonneuse dans la gueule de mon ami, en plein spectacle, ça va pas, c'est fini, j’arrête tout. Il savait lui aussi que c'était fini, que quelque chose venait de se terminer. A force de lui dire que demain il verrait, qu'il aurait le temps de réfléchir, il y est retourné pour finir le spectacle. La dernière chose que je lui ai dit avant de partir me faire recoudre, c'est : regarde le bon coté des choses, jusqu'à la fin de mes jours, je penserais à toi chaque fois que je me raserais...

Have you heard the story of the clown who had no nose ? No ? Well, let me tell it to you. When I felt the blow on my chin, I knew it was over. You can’t have the slightest idea of what being cut by a chainsaw is like until you go through it, above all when you get it in the gob, The gob is, by definition, the bit of your own body you get to see least of all. You might think that it cuts, but it’s not at all the same thing as a razor or a knife, the flesh isn’t cut cleanly, it’s not sharp as sensations go, nothing’s sliced. A chainsaw cut hits, rips, bites, claws. It’s a bit like being hit with a crocodile toothed baseball bat. It has to be said that having a cigarette cut from your mouth by a chainsaw as one big nose-thumb at traditional circus is a relatively risky business, involving a large dose of madness, that punk madness that was part of us then, the madness of this show, a bonkers translation of the madness of the world and the madness of the audience. Despite the utter briefness of the moment the number of thoughts that clambered through my mind is incalculable. The silence that surrounded us had something unreal about it. There we were, stuck in the middle of the ring, (stage, road), surrounded by over and above 2000 people, and yet I have to say it just happened to be one of the most intensely intimate moment of my entire life. One of those moments in which you know that your lives and the course of history have just tipped over. The memory of the look on Jason’s face, his arms hanging by his side, the chainsaw still smoking in his hand, that look, that look I’ll never forget... When I think of it now, some twenty-five years on, he seems to be saying something utterly different than what I thought I’d seen then. Today I’ve the impression that he was saying « Go free yourself, I’m saving your life, go while there’s still time, this is going to end badly, and you know it, so go, go. »... Whereas at that moment his face showed all the despair of someone who had by accident injured his friend. A look of infinite sadness, which needed to say so much but, given the circumstances, was speechless. Then again, the only thing he said after kissing me was « I think you’d better get out ». And I left, my final exit, the most beautiful, the most theatrical, the longest, the most silent, an exit for me and me alone in a thunderous silence, beyond time, beyond me, beyond everything. I felt the light and the heat from the follow spots as they clung to me, on the back of my head the held breath and the eyes of the whole company as I walked towards the exit, towards the exterior, in an unreal calm which was to cease at the precise moment I crossed the threshold. As long as I stayed inside, calm reigned, almost soundless and, for once, the fury was outside, but I had to go out, I had no other choice than to take on this « outside », knowing full well that once I had gone over to the other side I could never return, which was in fact what happened. I would have liked to press Pause, go back, stay there, a little, just a bit, but my life was waiting for me. At the very moment I pushed open the door the show re-started, I started bleeding like a stuck pig and the few people who were outside rushed at me. It felt really aggressive, I know it’s not what they meant but people who come at you full on just to tell you everything’s going to be alright, to reassure you, are anything but that. I told them all to sod off with great eloquence. All I wanted was a wing mirror, to see myself, see the extent of the damage but nobody would let me see my own face. I grabbed a hanky someone held out for me, put pressure on my chin to try and stop it bleeding, got into a car and looked at myself. A good scar on the chin, kind of lacy, like a staircase, an image of the story, and two tiny claw marks on the nose, tiny and huge at the same time, like an invisible threat, a chainsaw of Damocles, a mechanical growling saw hanging on the thread of my decisions. I refused to go to hospital straight away, I waited until Jason, Boris and the other metal clowns came offstage, I wanted to see Jason before I went, knowing he would be in pieces, eaten up, floored by guilt, I wanted to hold him in my arms, tell him look, it’s nothing, just a few stitches, nothing more. He was completely barmy, didn’t want to go on, didn’t want to go back in, he kept on saying I’ve just gone and stuck a chainsaw in my friends face, right in the middle of the show, it’s no good, it’s over, I’m giving up now. He too knew it was over, that something had just ended. By telling him over and over that he’d see about it tomorrow, that he’d take time to think about it later, he went back in to finish the show. The last thing I said to him before I went off to be sewn up was : Look on the bright side ; right up until the end of my days I’ll think of you every time I shave...

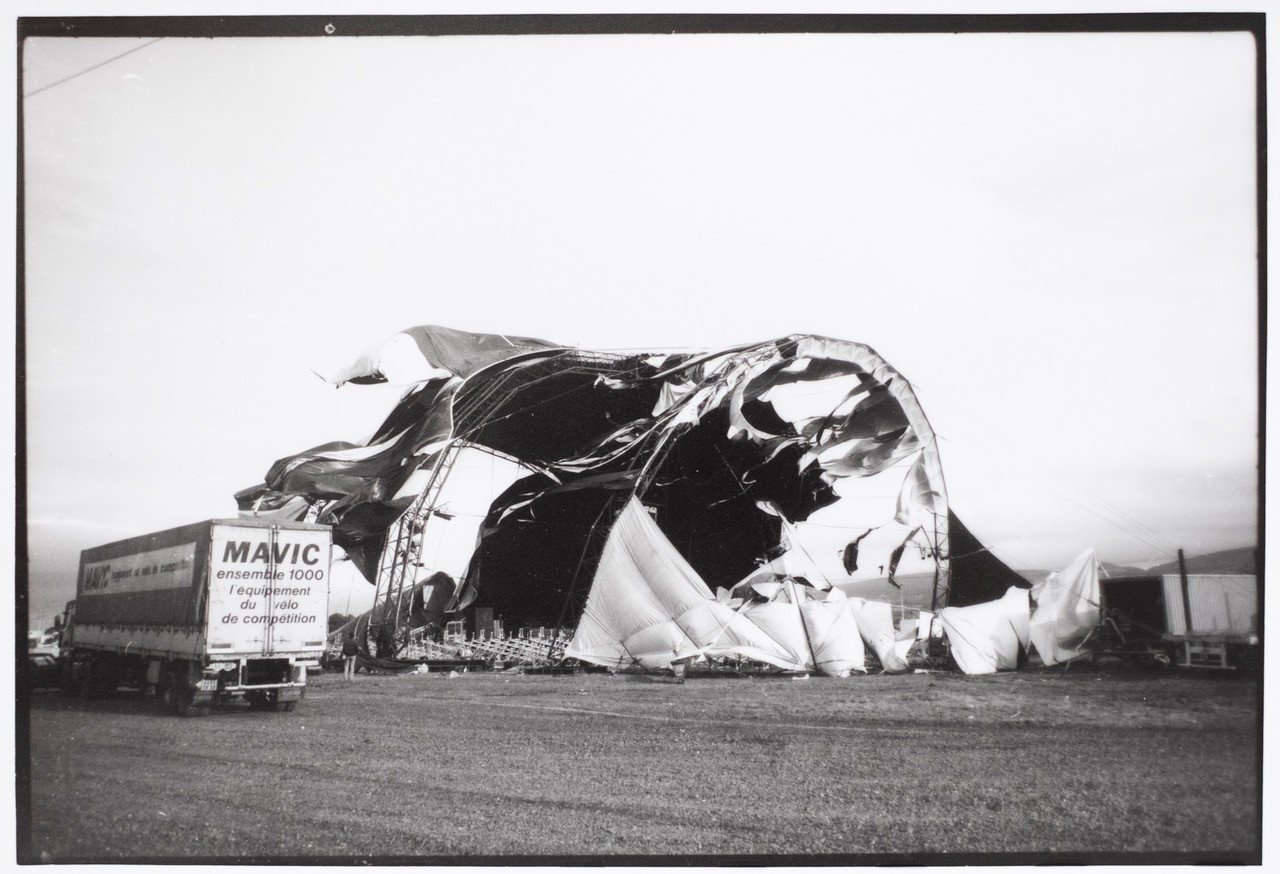

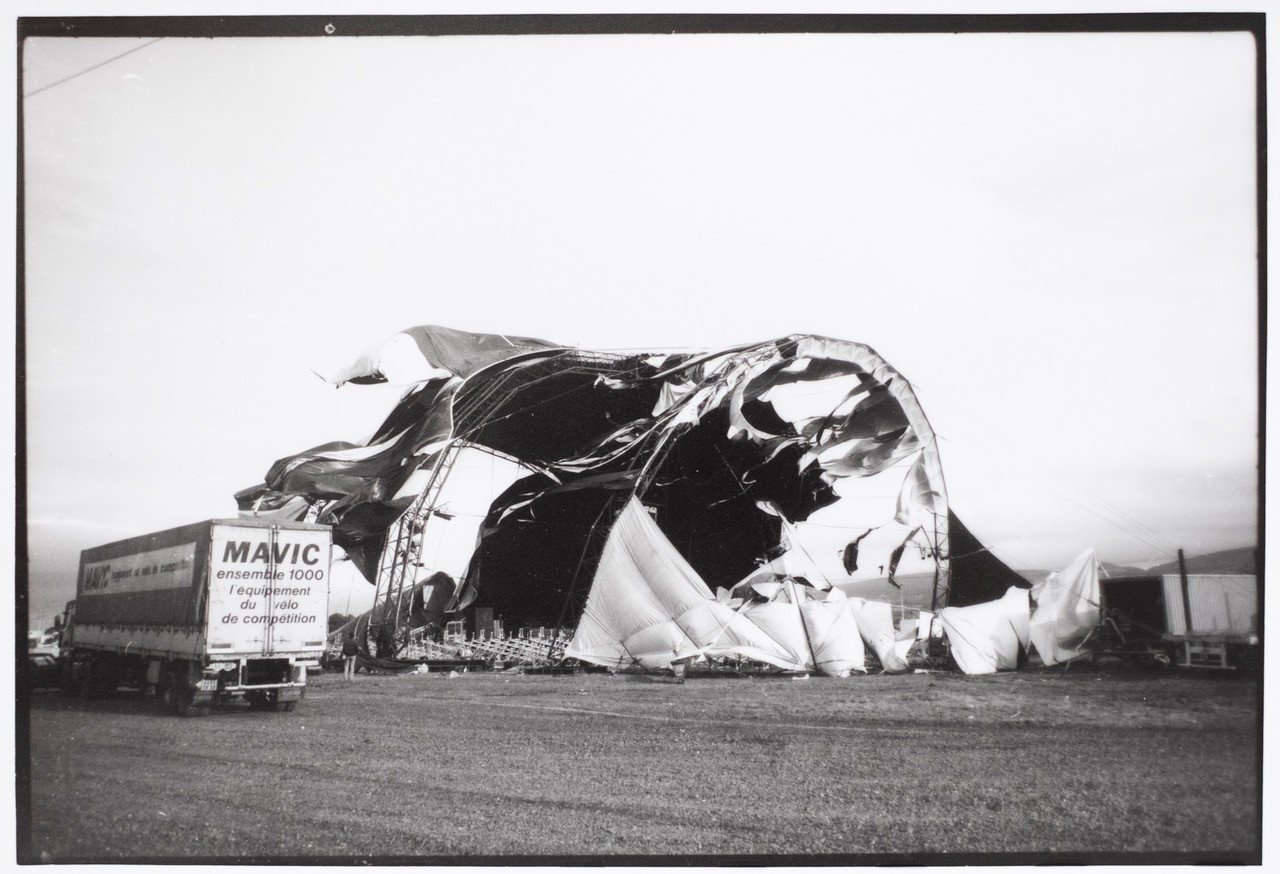

Show must go on Le chapiteau décharné rend l'âme Échoué comme une grosse baleine Contre une tempête infâme Il s'est battu à en perdre haleine La cathédrale squelette réveille en moi Avec ses lambeaux de toiles pendus Une folie qui me fait oublier la foi En écho à tous mes rires perdus La terre des Celtes nous condamne Il n'y a point de druide, ni de chêne Et le Thallag hurlant nous réclame De payer le prix de notre blasphème Sur mes épaules, trop de poids Je pose un genoux à terre, fourbu Hier au sommet, j'étais le roi...

Show must go on Le chapiteau décharné rend l'âme Échoué comme une grosse baleine Contre une tempête infâme Il s'est battu à en perdre haleine La cathédrale squelette réveille en moi Avec ses lambeaux de toiles pendus Une folie qui me fait oublier la foi En écho à tous mes rires perdus La terre des Celtes nous condamne Il n'y a point de druide, ni de chêne Et le Thallag hurlant nous réclame De payer le prix de notre blasphème Sur mes épaules, trop de poids Je pose un genoux à terre, fourbu Hier au sommet, j'étais le roi Et aujourd'hui, je suis vaincu C'est un jeu ou personne ne gagne Une vie qui n'est pas faites de flemme Mais j'ai dans mon cœur la flamme Et assez de sang dans les veines Alors, je me relève encore une fois Lentement, je fais le salut Je remet sur mon épaule ma croix Et le spectacle continu The gaunt big top gives up the ghost Stranded like a fat whale Against an infamous storm It's been fighting for breath The skeleton cathedral awakens in me With its hanging shreds of canvas A madness that makes me forget faith Echoing all my lost laughter The land of the Celts condemns us There's no druid, no oak tree And the howling Thallag calls on us To pay the price for our blasphemy Too much weight on my shoulders I'm down on one knee, exhausted Yesterday at the summit, I was king And today I'm defeated It's a game nobody wins A life not made of laziness But I've got the flame in my heart And enough blood in my veins So I rise once more Slowly, I make the salute I put my cross back on my shoulder And the show goes on Je n'y était pas, mais j'imagine... C'est le petit matin, il ne reste plus rien. La tempête s'est arrêté, mais le bruit des toiles déchirées claque encore dans ma tête. Je crois même que je vais les entendre claquer et se déchirer jusqu'à la fin de mes jours. Personne ne parle plus, le constat est trop profond, comme la blessure. La maison n'a plus de toit, la cathédrale de tissus en lambeaux laisse apparaître son squelette, le lieu de tout les possibles a disparu, l'écrin où on projetait nos fantasmes n'est plus là. On a tous des têtes bien pire que si on mettait bout à bout tous les lendemains de nos pires cuites. Nos âmes et nos corps sont marqué d'autant de cicatrices que la toile, c'est fini, tout est fini. La mort rode et elle est bien pire que la mort, parce que l'histoire est morte, mais nous, nous sommes vivant. Elle a seulement emporté notre raison de vivre, elle a emporté notre outil de travail, elle a brisé ce qui nous liait malgré nos différences, elle a disloqué nos espoirs, elle a fait disparaître les applaudissements, les rires, laissant place à ce silence si particulier qui succède aux grandes catastrophes. Et pour nous montrer qu'elle seule préside à notre destinée, pour nous montrer que son bras vengeur frappe là où ça fait le plus mal pour ceux qui croient être au dessus des ses lois, pour nous montrer ô combien nous sommes dérisoires, elle fauchera un peu plus tard, par surprise, une fois que tout sera rentré dans l'ordre, la plus faible d'entre nous, la plus fragile, la plus innocente, celle qui ne faisait pas tout à fait partie de cet univers, la lilliputienne. Quand je dis une fois que tout sera rentré dans l'ordre, en fait rien ne rentrera plus jamais dans l'ordre, malgré le montage d'un autre chapiteau de location (trop petit pour le camion trapèze), malgré de nouvelles toiles qui seront livrées un peu plus tard, un peu plus loin, malgré toute la bonne volonté, malgré tout... Le traumatisme sera trop profond et il donnera du recul, il laissera l'impression amère que nous avons embarqué sur un bateau beaucoup trop gros, un bateau dont nous avons perdu le contrôle, mais encore une fois, malgré tout, l'aventure continuera jusqu'au bout, jusqu'à sa fin, jusqu'à Paris. Avec l'image du trou béant de la grande bibliothèque en construction qui se rapproche chaque jour un peu plus du chapiteau, inexorablement, avec la sensation que forcément tout allait être englouti, tout allait disparaître. Comme si une fin à sa mesure, ou à sa démesure, attendait tranquillement, tapis dans l'ombre, pour happer le chaos lui même, pour l’enterrer profondément sous quelques milliers de tonnes d'une certaine culture, plus conventionnelle et surtout plus lourde. Un fin au bulldozer, une fin comme on les aime finalement. Quoi de plus logique pour la fin de Monsieur Chaos, des bruits de ferrailles qui hurlent leurs désespoirs, des moteurs grondants et fumants, des machines sans pitiés qui brisent le matériel et les hommes, les hommes terrassés qui courent dans tous les sens, de la sueur, des larmes et du sang mêlés, des bruits de dents qui grincent et des cris, des cris de terreurs et des cris de joie, comme un accouplement terrible entre les spectateurs et les acteurs, entre les amis et les ennemis, comme un orgasme final, comme une dernière scène qui se joue dans la vie, non pas sur la piste, une dernière débauche, un dernier acte d'amour et de haine, au terminus des rêves, au fond du cimetière, au fond de la casse, tout au fond, tout au fond... I wasn’t there, but I imagine... Early morning, there’s nothing left. The storm’s over, but the sound of the ripped tarpaulin still slaps inside my head. I think I’ll be hearing them whipping and ripping til the end of my days. No one speaks any more, the facts are too profound, as is the wound. The house no longer has a roof the cathedral, stripped of its flesh, lays bare its bones , there where all was possible has disappeared, the showcase where we laid out our fantasies is no more. We look as if all our lives’ worst hangovers have come to roost on us all at once. Our souls and bodies are as marked and scarred as the ripped tarp, it’s over, everything is over. Death is lurking and is well worse than death because dead is the story but we are still alive. She has taken our reason to live, the tool of our trade, she has smashed that which held us apart despite our differences, dislocated our hopes, she has wiped away the applause, the laughter, leaving in their place the particular kind of silence that follows great catastrophes. And to show that she alone is mistress of our destiny, to show us that her avenging arm hits where it hurts the most for those who believe themselves above her rules, in order to show us how unbelievably puny we are, she will mow down a little later on just for the surprise, once everything has gone back to normal, the weakest of our number, the most fragile, the most innocent, the one who wasn’t quite, not really a part of this universe, the Dwarf. When I say once everything has gone back to normal in fact nothing will ever really get back to normal, despite the rigging of another hired tent (too small to allow the trapeze truck inside), despite the new tarpaulin which will be delivered a little later, a little further, despite all the will in the world, despite all... The shock will be too deep and will give time to think, look back, it will leave the bitter impression that we’ve climbed on a boat way too big, one that we’ve lost the control of but once again, in spite of everything, the adventure will go on until it’s end, until Paris. With the image of the gaping hole of the great National Library in construction which creeps every day closer to the tent, inexorably, with the sensation that of course everything will end by being swallowed up, everything will go. As if a fitting end, or an unfitting one, was waiting calmly in the shadows, to gulp down the chaos itself, to bury it oh so deeply beneath several thousand tons of a certain culture, more conventional and certainly way weightier. Death by bulldozer, not bad as a way to go, the way we like it, finally. What could be more logical for the end of Mister Chaos, sounds of metal shrieking its despair, motors groaning and smoking, pitiless machines crushing things and men, beings brought to the ground and running this way and that, sweat, tears and blood mixed, the sound of grinding teeth and screams, cries of terror and cries of joy, a terrible copulation between the spectators and the actors, between friends and enemies, like a final orgasm , a final scene playing itself out in life, not in the ring, an ultimate debauchery, a last act of love and hate, at the terminus of dreams, the deep darkness of the cemetry, all the way down, all the way...

By Mark Borkowski

Composing this Requiem for a dear friend is made more difficult, knowing that I am missing his funeral as I write it. Any number of emotions envelop reasoning. Pierrot Bidon is dead. Long live Pierrot Bidon. It was impossible able to thank Pierrot. He gave me the opportunity to experiment in a genre of maverick hype that forged my early career in entertainment publicity. And now it’s too late.

Pierrot will always be the first name on my fantasy dinner party guest list. He would have a dual role: as a mischievous sprite to help create...

By Mark Borkowski

Composing this Requiem for a dear friend is made more difficult, knowing that I am missing his funeral as I write it. Any number of emotions envelop reasoning. Pierrot Bidon is dead. Long live Pierrot Bidon. It was impossible able to thank Pierrot. He gave me the opportunity to experiment in a genre of maverick hype that forged my early career in entertainment publicity. And now it’s too late.

Pierrot will always be the first name on my fantasy dinner party guest list. He would have a dual role: as a mischievous sprite to help create a unique ambience; and to help provide the food. Here’s the reason – on one memorable occasion, we discussed staging a party I wanted to throw for a long-forgotten reason. Pierrot enthused about creating a Bacchanalian feast. He envisaged a gigantic spit roast complete with a huge cow rotating under a vast fire, adjacent to the dining table. It would approximate a medieval banquet. Attendees would carve their own portions.

Pierrot was sardonically compassionate to the vegetarians with his meat-free option. He proclaimed that he would erect an infinitesimal spit, powered by a Heath Robinson motor and pulley system, which would gently roast a few mud-splattered carrots. This, surely, would keep the vegetarians happy? Non? Ah, the poetry of Pierrot’s barbeque and “after show” celebrations, they were legendary.

Food was of paramount importance to Pierrot. At one journalistic junket in Ales, Pierrot became excited by one of the bikers returning on a spluttering Yamaha with a sheep strapped to the bike with a discarded electrical flex. The sight of a rifle slung across the drivers bare back lead on scrupulous scribe to believe that they were witnessing a touch of “mutton rustling”. Peirrot assured the concerned hack that this was a normal shopping run. “We don’t go to the fucking supermarket; our food is fresh!”

If you ask circus folk: “How is business this week?” you’ll get one of two responses. If audience figures are reasonable the patron will shrug and say: “OK”. But if the tent is empty the retort is: “We starved this week.”

Historically, travelling shows depended on good houses to feed the troupe and Pierrot knew that he had to take responsibility for feeding his company. Good food produced a happy company. The mess was the centre of the circus family’s existence. And if there wasn’t any food available there was always red wine.

One journalist got very excited when Pierrot told him that he would bring 400 litres of wine into Britain to lubricate the tour. The preview piece ran in advance. The article was also read by Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise. The excise men tried to find the booze when the company convoy arrived in Dover. Despite their best efforts the fuzz failed to recover the stashed booze.

Pierrot was reminiscent of the circus folk that dispatch pragmatic wisdom learnt from the experiences of the road. Subversive and intellectually acute, Pierrot looked the part; a philosopher with a touch of gypsy, plus all the coolness of a leather-jacketed rocker. His gobbets of perception were delivered with an abundance of warmth and a laconic impish smirk, illuminated by a twinkle in his eyes.

The internet distributes bad news at lightning speed. Emails swarmed, news of his death flew inside cyberspace the instant he breathed his last. An extraordinary outpouring of love followed, from the Archaos Diaspora. If they did not know it before, the learnt something after his death; they were all entwined with an invisible chord, wrapping their hearts, conjoined with a communal love of the man. All those he touched were desperate to be united with brothers, sisters, lovers, comrades and companions insistent that the pay homage to the family patriarch.

It might have been easy to mistake him for the epitome of an alternative, creative, hard-drinking, hell-raising, larger than life character, but Pierrot had a softer, more contemplative persona alongside an insatiable appetite for life. He was an idealised self-portrait of a rebellious nonconformist with an undeniable predilection for low-key bravado.

One of Pierrot’s memorable aphorisms exemplified his inner soul: “It is important to be mad and crazy. We must not look on life as normal. I like it when they say you are not normal. I say it is important to be insane – it makes the world a more pleasant place.”

Edinburgh for many years was Archaos’s second home, pitching the party on the less fashionable side of the City at Leith Links. Leith served as the stage for many of Scottish history’s significant events. With splendid irony, the circus village was pitched on the remains of the battlefield of Scottish insurgency.

It was the perfect place – the company breathed life in to this downtrodden ghetto and created their own citadel. On the edge of the encampment stood the Port O’Leith. It was an old pub that needed a scrub, habituated by the underbelly of the city. The streets outside were adorned by ladies of the night.

Falling into the bar after a show, an unwitting imbiber would observe the company in full flow. They created an intoxicating, bustling bedlam. Later, Leith was given a huge amount of cash to help regenerate. Perhaps it would have been wiser if the procurement department had assigned the money to Pierrot; he would have made it matchless parish.

Pierrot had a knack for identifying interesting talent. A French Vogue journalist did not file his copy; instead, he joined the show. Antonia, a receptionist at the Groucho Club, ran away with the circus after one of my press briefings. There are too many examples to mention all. Pierrot allowed them all to stay until the made a mistake or their ego became bad for the company morale.

Misfits and wastrels found meaning in the show and everyone had an important creative part to play, everyone found themselves suddenly aquiring a purpose. But, as Pierrot put it: “The big difference is that traditional circus is without life, spirit and energy. And with our show, the public becomes attached to the characters who are performing – they fall in love with them.”

Pierrot knew how to be a slightly scary father. They company worked hard; young things (and old) played their part in the machinations of the production but, after hours, ran a hedonistic riot – sometimes creatively, sometimes not. On one occasion they staged a big after-show party, with Mano Negra playing an impromptu gig. In the early hours, some small fireworks were let off in the big top which was thought great fun. A few minutes later Pierrot appeared in his dressing gown and shouted: “Arrete!” And that was that.

He let his crew/family play, he encouraged creative anarchy – but, like a good parent, put his foot down when we overstepped the mark. There was the ethical problem – the attraction of circus is a voyeuristic thrill, which comes from the real possibility of injury or worse. But Bidon’s children clearly had an addiction to danger, which verged on the psychotic. Maybe Freud understood it when he said: “Where danger is, there is salvation!”

In fact the shambolic nature of their performance was partly an illusion. There was a split second method in their madness. Everything was precisely choreographed.

Influenced by Archaos, Cirque du Soliel is the most recognizable global Circus brand, a Disneyesque juggernaut that, like MacDonalds, weaves its lavish commercial magic across the seven continents. Cirque’s creator Guy Laliberte is one of the richest entertainment figures in the world. Pierrot would never be his commercial equal, but for those that met Pierrot or saw his shows, that peculiar magic that allowed Cirque to come into being will remain tattooed on their heart.

2010 will see celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of the great American showman P T Barnum. It is fittingly perverse that Pierrot should pass away in the same year. Pierrot was a folkloric hero, genetically connected to the American’s DNA. As an entrepreneur and impresario Barnum was more akin to Simon Cowell – Pierrot was closer to William Castle, the outlandish American B movie schlock film/producer/ director.

Pierrot was developing a new show, Place de Anges, which promised so much. Rather prophetically, it was a tale of a group of renegade angels granted a day release from heavenly bliss. This Wenderesque show was to be an excuse for wild, breathtaking acrobatics high above an audience mesmerized by their antics. As the show progressed and the stopwatch ticked, the celestial Cinderellas were to reconnect with mortal sin. Reacclimatized to earth’s physical distractions, their wings would start to molt, shedding feathers. As the show progressed the audience would have been engulfed in feathers.

As Pierrot talked me through the show, I chuckled at the thought of tracking down the requisite ton of clean goose and chicken feathers. I considered the Heath & Safety chaos, the avian flu hysteria. What a package! What a narrative! My publicist’s antennae were waving furiously.

I pray that his last show can and will be staged – we all need one last chance to remember the extraordinary genius of Pierric Pillot, aka Pierrot Bidon.

Mark Borkowski 2010

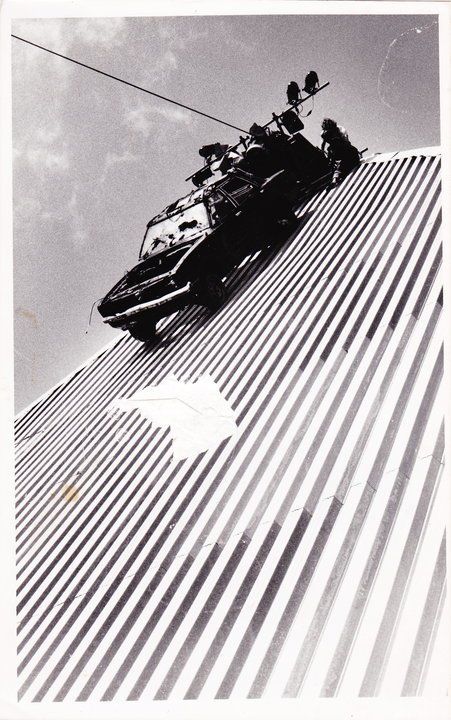

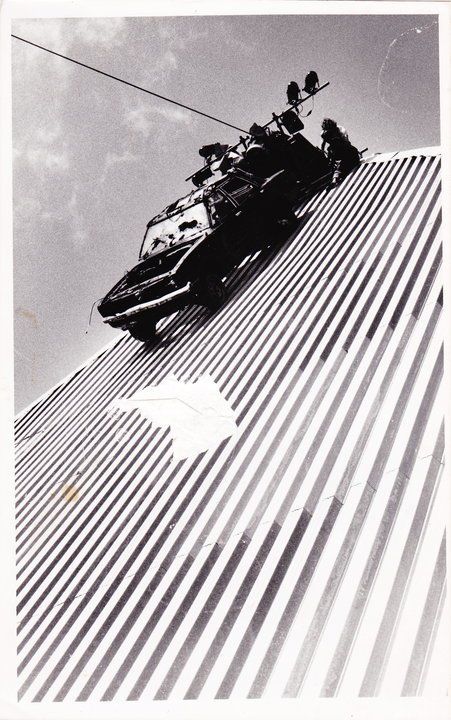

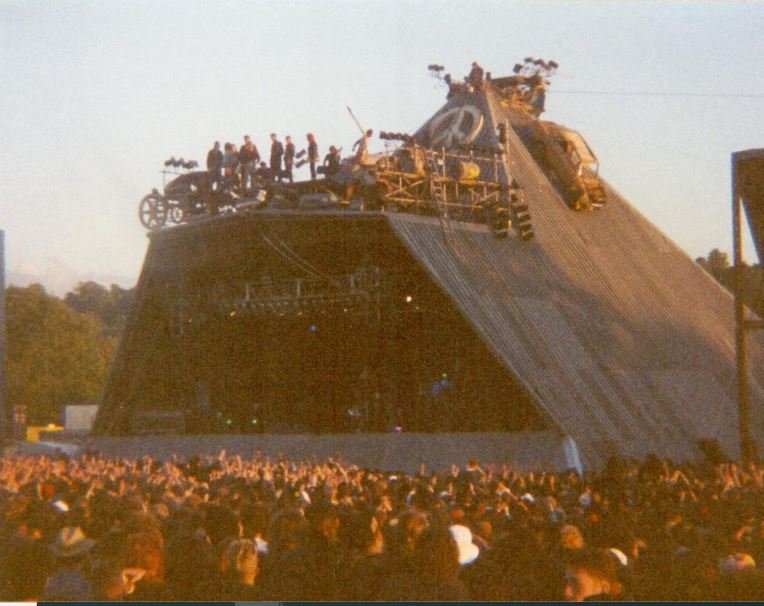

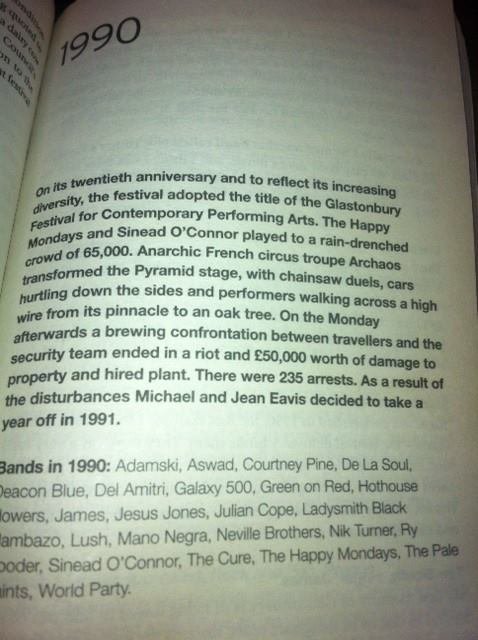

Archaos headlined the pyramid stage for all three nights of the festival in 1990.

From The Telegraph

In 1990 there was a real stunt at Glastonbury that knocks all the preceding examples into a cocked druid’s hat. A Frenchman called Didier Pasquette walked to the pinnacle of the Pyramid stage on a tightrope. It was part of a death-defying display by theatre troupe Archaos, who remain the only circus act to ever perform on Glastonbury’s main stage. People involved can still scarcely believe what they saw. “You couldn’t do it now. You just couldn’t get it past health...

Archaos headlined the pyramid stage for all three nights of the festival in 1990.

From The Telegraph

In 1990 there was a real stunt at Glastonbury that knocks all the preceding examples into a cocked druid’s hat. A Frenchman called Didier Pasquette walked to the pinnacle of the Pyramid stage on a tightrope. It was part of a death-defying display by theatre troupe Archaos, who remain the only circus act to ever perform on Glastonbury’s main stage. People involved can still scarcely believe what they saw. “You couldn’t do it now. You just couldn’t get it past health and safety. It’s a different world,” says Mark Borkowski, the PR veteran who looked after Archaos at the time. “More or less every performance with Archaos, somebody got injured.”

Pasquette didn’t. He was a world renowned tightrope walker who studied with Philippe Petit, who walked between the former Twin Towers in New York in 1974 (as immortalised in the 2008 film Man on Wire). And he stunned tens of thousands of fans waiting to see The Cure. “Anybody who saw it didn’t quite understand what was happening because it wasn’t billed, it was a big surprise. It was an art event in many ways,” says Borkowski. “The old Pyramid stage had a bit of a flat top to it. Didier walked up the side [on the wire], across the top and down the other side. He went to the pinnacle – there was lots of fire and explosions. And then The Cure came on.”

The event happened because Michael Eavis “was obsessed with Archaos, who between 1989 and 1992 were the most radical and life-changing act for many people, me included”, Borkowski says. Eavis has apparently said it was one of his favourite ever Glastonbury moments. “I don’t think they had any clothes on either,” recalled one witness, Polly Bradford, in 2004. It makes stencilling cows seem tame.

Chainsaws, fork lift trucks and semtex - In the 1980s the French ripped into the traditional circus format with a demented vitality that outraged authorities across the UK.

Archaos were the creation of Pierrot Bidon, "part gypsy, part street urchin, very hairy" according to Mark Borkowski. He was their British publicist, and saw it as his job to get them out of the cultural pages and onto the front pages instead.

"The Human Circus Hides Sick Secrets" - a typical tabloid headline that followed Archaos wherever they went.

As a result local councils banned them again and again, a...

Chainsaws, fork lift trucks and semtex - In the 1980s the French ripped into the traditional circus format with a demented vitality that outraged authorities across the UK.

Archaos were the creation of Pierrot Bidon, "part gypsy, part street urchin, very hairy" according to Mark Borkowski. He was their British publicist, and saw it as his job to get them out of the cultural pages and onto the front pages instead.

"The Human Circus Hides Sick Secrets" - a typical tabloid headline that followed Archaos wherever they went.

As a result local councils banned them again and again, a cunning ploy to sell huge numbers of tickets wherever they went.

Miles Warde tracks down the British participants who made Archaos more successful here than anywhere else.

He meets their producer Adrian Evans, and performers like Mischa Eligoloff who moved from backstage to fire-eater, hiccuped during a performance, and felt all his paraffin enter his lungs.

Or as Pierrot Bidon used to say, "A life without danger is not a life; a show without danger is not a show."

Producer: Miles Warde

First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in September 2010.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00tmtxs

(Link to programme)

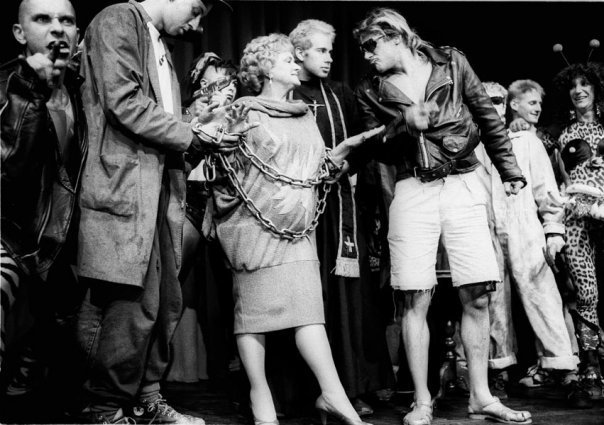

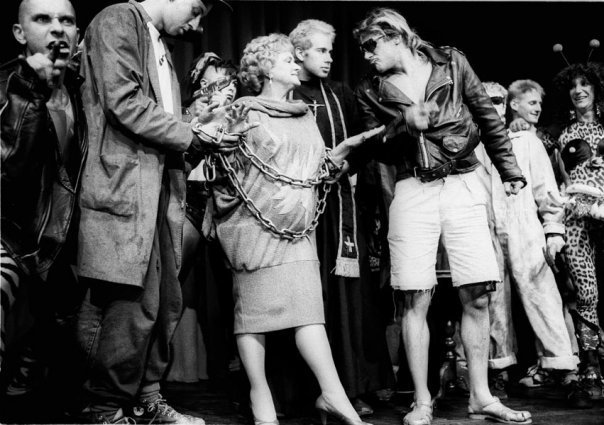

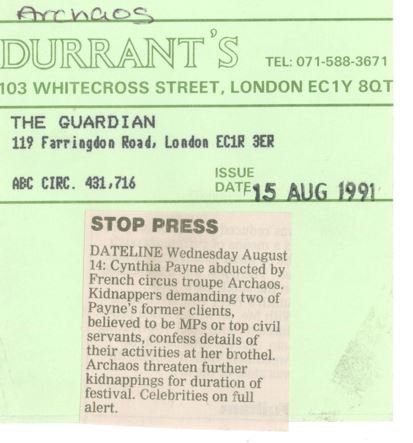

The night we nearly killed Cynthia Payne.

August 1991 the Edinburgh Festival. Archaos played the festival 3 years in a row. (89/90/91)

With so many shows on there was a regular scramble to get publicity, not that Archaos needed any as every show was sold out. For examples of the ‘noise’ created around the shows see the press files for stories such as ‘car in half’ and ‘Iraqi strongman quits circus to join war’ In 1991 the publicity plan was to storm Cynthia Payne’s one woman show which was playing in town.

Cynthia Diane Payne (24 December 1932...

The night we nearly killed Cynthia Payne.

August 1991 the Edinburgh Festival. Archaos played the festival 3 years in a row. (89/90/91)

With so many shows on there was a regular scramble to get publicity, not that Archaos needed any as every show was sold out. For examples of the ‘noise’ created around the shows see the press files for stories such as ‘car in half’ and ‘Iraqi strongman quits circus to join war’ In 1991 the publicity plan was to storm Cynthia Payne’s one woman show which was playing in town.

Cynthia Diane Payne (24 December 1932 – 15 November 2015) was an English brothel keeper and party hostess who made headlines in the 1970s and 1980s, when she was convicted of running a brothel. Known as "Madame Cyn", Payne first came to national attention in 1978 when police raided her home while a sex party was in progress. Men paid with luncheon vouchers to dress up in lingerie and be spanked by young women. Police found 53 men at her residence, in varying levels of undress, including "a peer of the realm, an MP, a number of solicitors and company directors and several vicars".

The troupe stormed the stage at the end of her performance, she was chained, and demands were issued. She was brought back to the Archaos tent where a makeshift throne had been made for her, the throne was made from a truck tyre with a tatty old armchair from a skip on top. She was due to be chained there for the evening show. Fortunately for us and very fortunately for her she fell ill and had to be released prior to the show.

That evening the show started as per normal with the Bouinax praying to a stationary car in the middle of the piste. As if by magic the car springs to life and starts (Susie in the boot pressing a button) unfortunately some idiot Bouinax (no name - take your pick) has left the ghost car in gear so when the starter button was pressed it not only started but also flew forward smashing into the makeshift throne. The crowd went mad thinking it was part of the show, unbeknown to them if the throne hadn’t been there the front 5 rows of crowd would have been ‘taken out’ and Madam Cyn would have been a gonna if she had hung around. That evening a fence was built with Scaff around the piste in case it happened again.

Live music integral part of any Archaos show

Les Marcel Burin - Last Show on Earth & BX-91

Chihuahua - Bouinax

The Thunderdogs - Metal Clown

Live music integral part of any Archaos show

Les Marcel Burin - Last Show on Earth & BX-91

Chihuahua - Bouinax

The Thunderdogs - Metal Clown

September 30 1991 - Joe Strummer front the Pogues in the Archaos Tent - Toronto ..Check him out in his Archaos t-shirt. After the gig there was quite a party.

September 30 1991 - Joe Strummer front the Pogues in the Archaos Tent - Toronto ..Check him out in his Archaos t-shirt. After the gig there was quite a party.

From the book Pierrot Bidon L'homme cirque

ourtant, tout a encore des allures de rêve. Pierrot se rend à Dublin avec Pascal Bernardin pour rencontrer Bono et le staff de U2 qui souhaitent lui confier la direction artistique du U2 Zootour. Ce jour-là, la reine d'Angleterre n'est pas sa cousine.

Ils sont au moins douze autour de la table de réunion. Ambiance business et rock n' roll. Pierrot écoute attentivement, pose des questions, note, crayonne. Immédiatement, les idées surgissent : la présence des « trabans », l'arrivée sensationnelle de Bono... Pierrot exprime sans réserve ses visions, « I...

From the book Pierrot Bidon L'homme cirque

ourtant, tout a encore des allures de rêve. Pierrot se rend à Dublin avec Pascal Bernardin pour rencontrer Bono et le staff de U2 qui souhaitent lui confier la direction artistique du U2 Zootour. Ce jour-là, la reine d'Angleterre n'est pas sa cousine.

Ils sont au moins douze autour de la table de réunion. Ambiance business et rock n' roll. Pierrot écoute attentivement, pose des questions, note, crayonne. Immédiatement, les idées surgissent : la présence des « trabans », l'arrivée sensationnelle de Bono... Pierrot exprime sans réserve ses visions, « I see a cross in flames », dans son anglais de cuisine avec son accent à couper au couteau. La discussion dure des heures. Durant tout ce temps, le thé coule à flots. Bono, très british, fait office de maîtresse de maison : « Pierrot, do you want some more tea ? ». Et celui-ci décide de boire son thé, sans commentaire, totalement absorbé par l'enjeu créatif. Mais à la fin de la réunion, au moment de partir, alors que sur le pas de la porte s’envisage la prochaine rencontre, Pierrot pose la main sur l'épaule de Bono et lâche, aussi flegmatiquement qu'un pur britannique :

« Next time, my dear Bono, we meet in a pub, cause I want a pint of Guinness! ».

Les échanges sont multiples, l’enthousiasme de la production de U2 est à son comble, Bono évoque leur collaboration dans la presse, le dossier artistique et technique détaillé est produit par Pierrot mais bientôt...

Il n'y aura pas plus de Guinness que de beurre en branche (du moins avec Bono).

Dans les carnets de Pierrot se trouve, soigneusement collé et commenté, le billet du concert du fameux Zooropa Tour auquel il a assisté avec Ana. Ce qu'il a bien vu, depuis sa loge, comme les millions de spectateurs, ce sont les trabans, le décor de l'usine... .. ses propres visions. Pierrot en conçoit une certaine amertume mais surtout un sentiment de tristesse, celle de ne pas pouvoir aller au bout d’une histoire

C’est pourquoi, à Pascalito Voinet qui s’insurge contre les plagiats, il répond avec la distance et le fair-play qui le caractérisent : « Tu sais, Gégé, en général on copie les bons et ce qui est déjà fait. Qu’est-ce qu’on en a à… de s’attarder sur le passé ? Faut regarder devant, même quand c’est sombre sinon on devient des vieux cons. Nous, nous travaillons sur des projets. Alors au boulot !

Translation:

everything still has the appearance of a dream. Pierrot goes to Dublin with Pascal Bernardin to meet Bono and the U2 staff, who want to entrust him with the artistic direction of the U2 Zootour. On that day, the Queen of England is not his cousin.

There are at least twelve people around the meeting table. The atmosphere is business and rock 'n' roll. Pierrot listens attentively, asks questions, takes notes, and sketches. Immediately, ideas emerge: the presence of the "Trabant" cars, Bono's sensational arrival... Pierrot expresses his visions without reservation, "I see a cross in flames," in his kitchen English with his thick accent. The discussion lasts for hours. Throughout this time, the tea flows freely. Bono, very British, acts as the host: "Pierrot, do you want some more tea?" And Pierrot decides to drink his tea, without comment, totally absorbed by the creative stakes. But at the end of the meeting, as they are about to leave, with the next meeting in mind, Pierrot places his hand on Bono's shoulder and says, as phlegmatically as a true Briton:

"Next time, my dear Bono, we meet in a pub, 'cause I want a pint of Guinness!"

The exchanges are numerous, the enthusiasm of U2's production team is at its peak, Bono mentions their collaboration in the press, the detailed artistic and technical dossier is produced by Pierrot, but soon...

There will be no more Guinness than butter in the branches (at least with Bono).

In Pierrot's notebooks, carefully glued and commented on, is the ticket to the famous Zooropa Tour concert that he attended with Ana. What he saw, from his box, like millions of spectators, were the Trabant cars, the factory setting... his own visions. Pierrot develops a certain bitterness but above all a feeling of sadness, that of not being able to see a story through to the end.

That’s why, to Pascalito Voinet, who protests against plagiarism, he responds with the distance and fair play that characterize him: "You know, Gégé, generally, people copy the good stuff and what’s already been done. What’s the point of dwelling on the past? We have to look ahead, even when it’s dark, otherwise, we become old fools. We work on projects. So, let’s get to work!"

Click Here to access

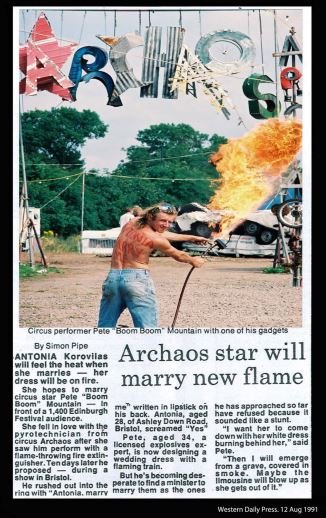

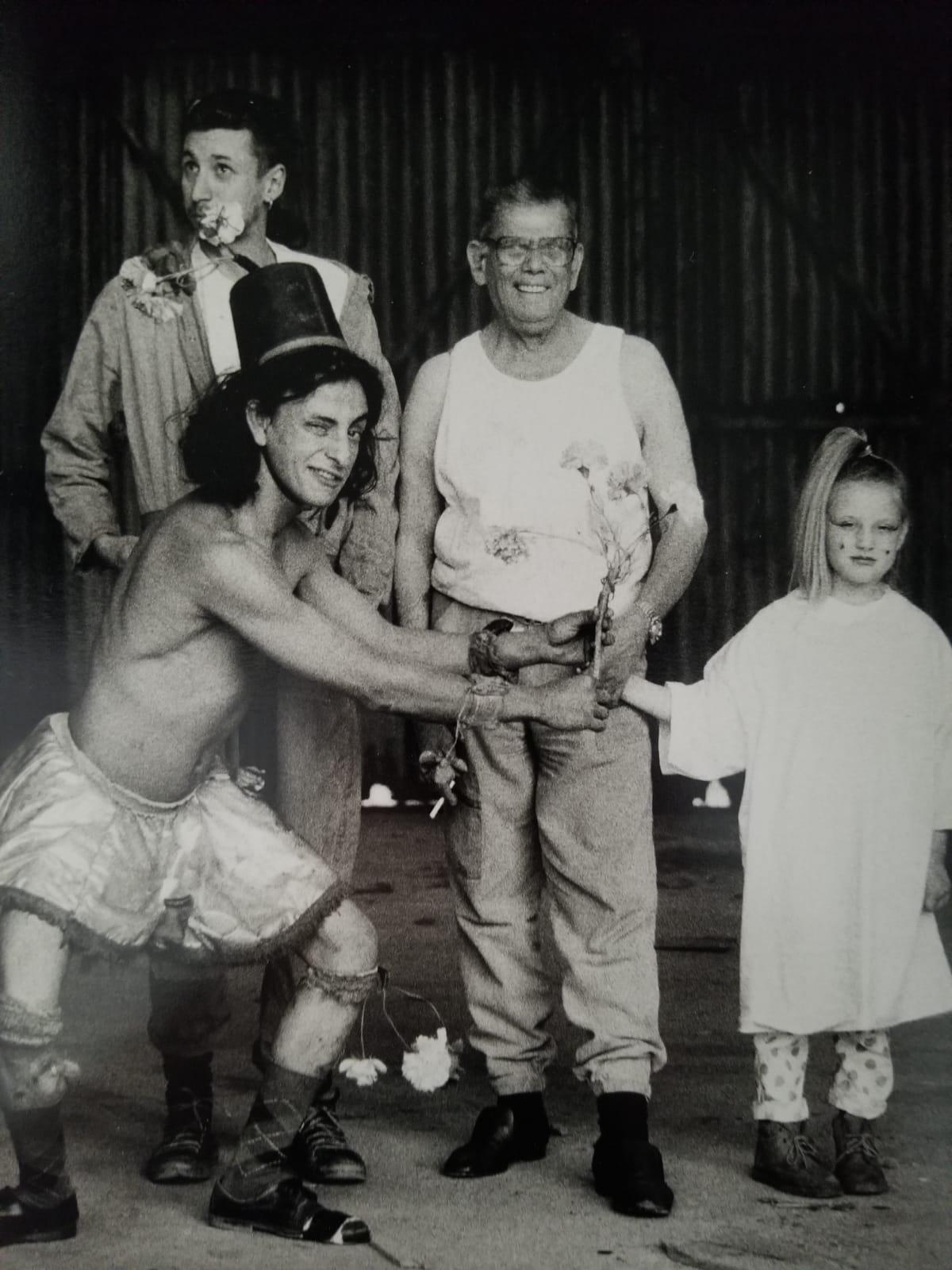

July 1991 Bristol – Archaos are in Brislington a suburb of Bristol which smells of vanilla ice cream (Tarr’s ice cream factory is there)

Circus pyro genius Pete ‘Boom Boom’ meets Antonia in the bar after a show, then at a party the troupe end up at….A few days later he proposes by stripping off his Bouinax jacket off during a show and revealing the question ‘Antonia will you marry me?’ scrawled in lipstick across his back..

Fast forward a few weeks and Archaos are on Leith Links Edinburgh (which doesn’t smell of ice cream) headlining the festival –...

July 1991 Bristol – Archaos are in Brislington a suburb of Bristol which smells of vanilla ice cream (Tarr’s ice cream factory is there)

Circus pyro genius Pete ‘Boom Boom’ meets Antonia in the bar after a show, then at a party the troupe end up at….A few days later he proposes by stripping off his Bouinax jacket off during a show and revealing the question ‘Antonia will you marry me?’ scrawled in lipstick across his back..

Fast forward a few weeks and Archaos are on Leith Links Edinburgh (which doesn’t smell of ice cream) headlining the festival – Saturday night and it’s a wedding – the finale of the show Antonia emerges on a forklift with dress on fire, a local rev conducts the service – they are pyro and wife – what follows is one of those legendary parties (no one remembers anything) a full sit down meal for 200 (not including Sean Connery who was in the audience but not invited to the wedding party) - the next days matinee was a bit of a right off.